Deutsche Version

Mel Gibson’s latest film, The Passion of the Christ (2004), has proven to be one of the most controversial films of recent times. The film has been accused of anti-Semitism since, according to some, it ventures to portray how guilty the Jews supposedly were in causing the death of Christ. Furthermore, the relentless depiction of violence with which we, as the audience, are confronted with, only increases the problematic notion of what Gibson calls the “blame game”. Even before the film reached the editing table numerous theologians and religious leaders (all of whom were not of the same opinion) joined critics in declaring the film religious slander. As a Protestant, I however wish to approach the film from a different angle by focussing on film as art within the religious experience.

Seen from a hermeneutic point of view, several perspectives exist with which viewers may interpret a work of art. Therefore it is understandable that accusations of anti-Semitic propaganda were made against the film and its director. This is simply the hermeneutical horizon one has to keep in mind when dealing with the evaluation of such delicate subject matter. It does not however exclude the possibility that some arguments in support of this anti-Semitic interpretation, may themselves at times appear to be “pathetic and often also laughable”[1]. Many commentators noted that the sheer fact that a Romanian Jewess, Maia Morgenstern, whose parents experienced the Nazi Holocaust firsthand, played Jesus’ mother, points to the unlikelihood of such an interpretation. But this is not an artistic argument as such. Still, the film as a whole does in fact suggest a clear non-anti-Semitic stance. One example is the scene in which a Roman soldier calls Simon a “Jew” in a way that denotes such disgust as to be pure anti-Semitism. Now this rather evokes a deeply embedded sympathy towards the Jews and a definite disgust with the way in which the Roman occupants regard the Jews.

Gibson himself quite rightly reacts rather irritably when confronted with this particular subject. In answer to a question by an Italian journalist, Gibson voiced an interesting counter-question with which nobody seems to reckon: “Did you think the film was anti-Roman?”[2]. Of course not. The post-Auschwitz perspective is now made a sine qua non for the whole world. The blame for the terrible events that occurred at Auschwitz is however not to be placed on the whole world. Neither is it the guilt of Christianity as a whole or of the Christian faith. It is the guilt of Nazis who sometimes in the name of Christianity but often in decidedly anti-Christian ways misused Christian faith to suit their aims. It is understandable that German theologians feel responsible for these events and need to come to terms with their history, and can therefore hardly approach films otherwise than exclusively from this angle. It is to be respected – perhaps it is the burden of their fate. At the same time however, they should also respect those whose opinion differ from theirs. There are also other perspectives that do not deny the seriousness of anti-Semitism, but do not deserve to be accused of it simply because they are different. These do not become illegitimate because there are Germans needing to come to terms with their past – not even when some among the latter apparently find it easier to cope when they can make the whole Christianity co-responsible. Is this not just as much an expression of apportioned blame?

The Passion of the Christ is a Christian film, not least because it is clearly orientated by the tradition of the Holy Communion. It also forces the audience to consider in a work-immanent way whether Jesus went the Via Dolorosa in terms of the Lord’s Supper. Seen from a dramatic point of view the answer is indisputably “yes”. Therefore, the cause of his suffering is collective human sin. Is this not the foundation of the Christian creed? Did the Son of God not suffer and did he not die for all humanity? In the film this notion is communicated both positively and negatively. On the one hand, Jesus expresses it in the hermeneutically central scene in which his disciples receive their first Communion: “This is my body, which is given for you” – first for Jews and subsequently also for the rest of the world. On the other hand, the Devil is forced to acknowledge that: the sins of all human beings fall on one man. Biblically, it is correct that Judas betrayed Jesus and that the priests accused him of sacrilege, but Pilate also carries a great deal of guilt (if one has to speak of “guilt”). It is said that Gibson portrayed Pilate in a very sympathetic way. Exactly the opposite can also be argued. One can also claim that the film depicts him as a total coward. What is agreeable in a man who knew he could prevent the torture and death of Jesus, but lacked the courage to act according to his conscience?

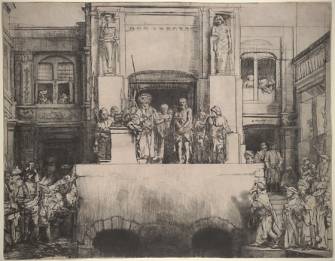

The fact that the priests appear to be visually unsympathetic, is also not a Gibsonian fabrication, but is artistically explicable. In studying the expressions of the Jewish priests (belonging to one Jewish party), one here recognises, as in the Pilate scene, clear influences of Rembrandt. In many ways one could thus speak of an artistic quote[3]. It is unlikely that any pastor would insult Rembrandt as being blotched up (given the knowledge that a picture is a Rembrandt).

|

|

Within the film’s narrative framework, an important fact to consider is that the director accentuated belated remorse in that the “culpable” realise the fateful consequences set in motion by their actions: Judas is haunted by his contrite conscience in the form of demonic children and consequently takes his own life; the priests finally comprehend the sheer magnitude of the events and weep; the majority of the Roman soldiers appear to be deeply affected by the Jesus’ death, although admittedly less than the priests. The way to Calvary not only leads from life to death, but is also dotted by several stations where the Son of God is tortured by humankind – physically as well as psychologically. Frankly, I find the primary power of the film most of all in the fact that the experience Christian faith is made immediate in the portrayal of Jesus’ gigantic self-sacrifice. Only those can find the film’s purpose in a search for scapegoats who need such an interpretation. In other words, those elements in the film that have been attacked so heatedly, can also be understood as the basic tenets of the Christian faith. As a convinced Protestant I therefore dare to claim that the film is already meaningful simply because, through its bare controversy, it has managed to vitalise a new interest in Christianity – something few religious leaders known to me can claim about their own careers.

Within this controversy the intention and artistic power of the film become clear. It is said that when a film claims to be historically accurate, it automatically abandons the artistic realm, since a work of art can only be created by fantasy, that is, the soul. The creative result thus becomes fiction. This holds good for the narrative art of the biblical Gospels as it does for any film. “History” becomes “his story”. The artistic portrayal of the Christian faith has always been an inherent part of our religion, and Gibson’s interpretation of the Passion belongs to religious art, which started with the evangelists. This fits quite closely with the function of artistic freedom. The film was inspired by the narrative as well as the visual arts within Christian tradition. According to its cinematographer, Caleb Deschanel, the film was greatly influenced by the work of Dali and Caravaggio. Deschanel also spoke about the visual power of the film: “At the Pamphilli Palace in Rome, there is a whole collection of paintings that are [lit by] candlelight. I studied those a lot, and I also went to places where I could examine things under firelight and moonlight. You’re not creating reality or naturalism, you’re creating the illusion of something, an impression. In that way the film is a metaphor for the time. The olive garden has a mystical quality, but somehow you accept it. It’s the same with the firelit scenes – we just wanted to create the illusion that it was real”[4]. This is removed from how-it-really-was-fundamentalism by miles. Not to forget, of course, the above-mentioned Rembrandt inspiration[5].

The violence in the film also has its religious as well as artistic reasons. From a religious point of view, the merciless and extremely bloody torture all the way to Golgotha plays a necessary role in the Christian experience of the Gospel. The catholic tradition (to which Gibson belongs) depicts the Passion of Christ (as it does his birth) as an idyllic, sterile event. However, also “decent, civilized” Protestants are not keen on being disturbed in their neatly set out religious beliefs either. True appreciation of the greatness of God’s sacrifice has become dull and blunted. It is hardly a deeply felt religious experience anymore and is therefore not taken seriously. On viewing the film, we are not merely audience members of a distant occurrence, but we become involved in the horror and we feel the pain. Many viewers take this so hard that they rather remonstrate against the film. On watching the film I too have shuddered at the sheer violence with which Jesus was tortured and crucified. Yet to me this confirms the words of Goethe’s Faust: “Shuddering is the best part of being human / However the world begrudges one the feeling / Moved within one deeply feels the Tremendous”: Christ suffered for me. According to Paul, it is I who have been baptised into Christ’s suffering and death. I can now experience what exactly this means. It was – it is – something terrifying. Understanding what suffering really entails cost a horrific price. If God had to leave his majesty in order to experience that which humanity is feeling and had been feeling for thousands of years (especially at a low point such as Auschwitz), then it can be nothing but horrific. Violence is no answer to our conflicts only because it has been concentrated in God’s own experience. That is the answer.

The way I understand my faith, is that this is exactly what the Protestant doctrine of the Holy Communion aims at achieving. We are relentlessly asked to listen and see just how mercilessly his body was broken and his blood spilt. Is the symbolism of the Sacrament more humane and less gruesome than Gibson’s filmic symbolism? Can we still shudder at the thought of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice? Or have we been desensitized? To put it differently: Do we still take it deeply seriously? The death of Christ is not merely a religious “story” which we hear every now and then in church (if we still go there), but it becomes an existing religious experience within the world of a Christian. If the Calvinist “real union with Christ” and the Lutheran hoc est or Johann Sebastian Bach’s gruesome “Head of Blood and Wounds” do not exactly mean this, then what do they mean?

In this context the juxtaposition of the crucifixion and the Last Supper is an effective directorial decision. First, Gibson focuses on John, who looks at Jesus’ hands as they are nailed to the cross and remembers, through a flashback, the Last Supper where Jesus used his unscathed hands in order to effectively bring a message across. Then, we see Jesus’ beaten body being hoisted up, that is, lifted up like the Host is lifted in the Catholic liturgy. This is again suggested by means of a flashback before we see the blood of Christ flowing down his body in a close-up. Subsequently, Jesus presents the disciples with the cup, which signifies the reality of his spilt blood. Gibson therefore not only presents us with a reason for the relationship between the Holy Communion and the core of the Christian faith, but he also succeeds in summing up the faith by means of visual images. All of this by no means implies that the resurrection has been overlooked, as some intimate. The shocking nudity of the resurrected Jesus heaves the victory over violence and death to its high point – which is a mystery and therefore can only be suggested.

The Passion of the Christ is therefore, despite certain “errors” of historical reference, as for example the use of Latin instead of Greek in the scene between Pilate and Jesus, a film that interprets an ancient story in an artistic and contemporary way. Just how contemporary this interpretation truly is can be seen in the current debates surrounding the film. In the end, the purpose of a good film is to forge an idea, thought or conviction, with the numerous aspects involved into an integrated and striking unity, by means of visual images. Just how hard Mel Gibson did strike with his The Passion of the Christ is eloquently attested to by the agitation of the agitated. The fact that there are Jews among them, is to be understood and respected in the light of the horrific events Jews had to endure by the hand of many Christians during the Holocaust. But the resentment against the interpretation of ostensible Jewish responsibility for the death of Christ has by no means been caused by Gibson, but by the church itself. That is why this resentment has for centuries been felt towards the symbol of the cross itself. Within the church people cannot rid themselves of this by passing on blame – for instance having Mel Gibson carry it vicariously so that church leaders can go free. They might just find that the people will not call for their release.

Church leaders, who are supposed to serve the spreading of the Gospel, have to accept an additional culpability. They have muffled the joyful message. To many of my generation it has become inaudible. We do not understand the language of the church. We do understand Gibson’s. Where does the absence of the younger generation glitter more – in church or in the cinema? Is the ecclesiastical establishment only its elder brother’s keeper? Or also of its own sons and daughters? We too are blood of their blood. In the most violent and bloody book known to me, the originally Jewish and later christianized Holy Scripture, we read about blood coming upon the heads of the really guilty. There, God threatens his prophet that the blood of those who come to a fall because of inadequate delivery of his message, will be required from the messenger. I think Mel Gibson can feel less fear for this threat than many of his ecclesiastical critics, who have always been pious.

Dr. Reina-Marie Loader

Department of Film Studies

University of Reading, England

English version of a German article published in the Austrian journal Saat, 13 June 2004.

[1] This expression was used in a German article by Austrian church leader, Dr M. Bünker, “When Mad Max gets pious: The Passion of the Christ – A ‘Jesus-Schocker’ in our Cinemas”, Reformiertes Kirchenblatt 81/4 (2004), p. 4.

[2] J. Cooney, Total Film 88 (2004), p. 72.

[3] So J. Phelan, The “Look” of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, electronic publication: www.artcyclopedia.com/feature.html (15.04.2004).

[4] S. Pizzello & R.K. Bosley, A Savior’s Pain, American Cinematographer 85/3 (2004), p. 55.

[5] So J. Phelan, The “Look” of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, electronic publication: www.artcyclopedia.com/feature.html (15.04.2004).